'What a lovely surface'

In the first of a series of pieces about treasures in the University of Cumbria’s Special Collections, we shares a glimpse of drawings admired by Charlotte Mason

Fred Yates expected to paint Charlotte Mason’s portrait when he arrived in Ambleside in 1901. The principal of the House of Education had invited the artist to do just that after meeting him at her friend’s house in London.(1) It’s less likely that he expected to cover the walls of a lecture room with drawings of works by Jean-François Millet (1814-75).

Yates had been lecturing on the French artist since at least 1889.(2) When he was asked to give a talk to Charlotte Mason’s governesses-in-training during his Ambleside visit, he wasn’t fazed by the fact that he lacked reproductions of Millet’s paintings to illustrate his lecture. Instead of using slides, he drew copies of paintings on the freshly white-washed walls of the building that would become known as ‘Millet’.

According to The Story of Charlotte Mason, Yates imagined his drawings being rubbed out even as he contemplated making his first mark: ‘“What a lovely surface,” he said. “Charcoal will easily rub off.”’ Charlotte Mason, however, ‘insisted that the drawings should be fixed to preserve them for students to come.’(3) Thanks to her decision and more than a little luck, nine of his drawings survive in ‘Millet’ today.

The Sower

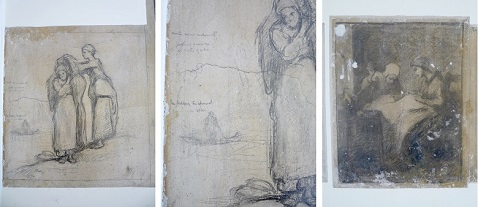

‘The Sower’ strides out in pride of place over the cooking range, flanked by what appear to be copies of studies for ‘The Washerwomen’. Yates knew Millet’s compositions very well indeed: compare the image of ‘The Sower’ here, at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, with the drawing in ‘Millet’. Look closer and you’ll see notes and sketches of the shapes of heads hovering at the edges of the drawings (see centre image below).

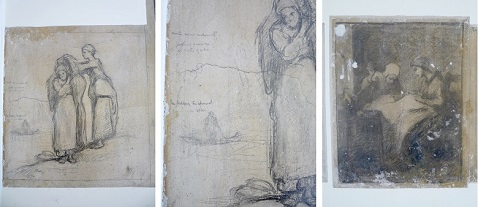

Some of the drawings bear scars, presumably caused by building work that took place while the images were hidden behind wallpaper or hardboard. The damage is regrettable, but it’s remarkable that so much has survived more than a century of daily life as part of the building’s fabric. These drawings give us a revealing glimpse of the House of Education in Charlotte Mason’s day – its cultural contexts as well as its physical environment. Together, the drawings and the building – the Millets in ‘Millet’ – link local histories of education and art in fascinating ways.

The Washerwoman

In what is now the second room on Millet’s ground floor, we find drawings with subjects including women sewing, three farm labourers at rest, a shepherd, and a figure tending a cow (perhaps ‘Peasant Watering her Cow’). Here too is ‘Feeding the Young’, sadly damaged but still visible. This piece provides both an image of maternal care and a figure for intellectual and spiritual nourishment; it might have struck a chord with Mason’s students and teachers.

Why did Yates choose to copy the works he did on the classroom walls? He may have been alert to their connections with both his audience of teachers-in-training and the rural communities of the Lake District, or perhaps he was simply drawing the images he needed for a tried-and-tested lecture. Whatever the reason for his choices, the House of Education provides a number of the drawings with a particularly resonant context. Yates may even have seen parallels between rural life in Ambleside and Millet’s Barbizon.

Millet was one of the artists attracted to the small village of Barbizon on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau. The ‘Barbizon School’, as they came to be known, were ‘pioneering painters of nature’ who ‘embraced their native landscape’.(4) Yates admired Millet greatly; a report of one of his lectures gives us a sense of what he valued in Millet’s approach to his rural scenes:

Millet himself worked in the fields until he was eighteen years of age, and well understood the constant struggle to earn a bare subsistence from the soil. He painted the peasant class at their work; and when accused of missing the beauties of nature, he protested that he saw the beauty in every flower, but he could not but see the tragedy and struggle which these beauties surrounded. […]

When [‘The Sower’] was exhibited at the Salon it created very strong feeling, many people declaring that Millet was a socalist [sic] and revolutionary – cursing the capitalist. But he declared, ‘I am only painting life as I see it.’(5)

Charlotte Mason’s desire to preserve the Yates’s drawings is hardly surprising given his skill as a draughtsman and the importance she placed on ‘picture study’. As many readers will know, Mason believed that children benefitted from studying reproductions of the works of famous artists as part of their schooling. Children were encouraged to study the pictures and then describe and discuss the stories they found there. For both Mason’s students and the children they taught, pictures were an important part of the learning environment.

Yates’s Millet drawings were part of daily life at the House of Education; images that Charlotte Mason’s students lived with and came to know well. Their more recent history is something of a mystery: we would love to hear from alumni who have memories of the ‘Millet’ building or Yates’s drawings. How do you remember ‘Millet’? You are part of the story too!

Article by Becca Weir

At present, the ‘Millet’ building is closed to the public and members of the University, but group viewings can be arranged by appointment: in this way, we hope to share the drawings safely, with interested visitors and alumni. Please address enquiries to Joanne Lusher alumni@cumbria.ac.uk

- Margaret A. Coombs, Charlotte Mason: Hidden Heritage and Educational Influence (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2015), 204

- John Hodkinson, The Yates Family, 1854-1920 (2002), 29 <http://www.rydal.org.uk/rydal-in-the-past/the-yates-family/fred-yates-legacy.html>

- Essex Cholmondeley, The Story of Charlotte Mason (London: Parents’ National Educational Union, 1960), 85

- Dita Amory, "The Barbizon School:French Painters of Nature" in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000-. <http://netmuseum.org/toah/hd/bfpn/hd_bfpn.htm> (March 2007)

- E M Hall, Lecture on Millet by Mr Yates, L’Umile Pianta (June, 1905), 55 <https://www.redeemer.ca/acadmics/library/charlotte-mason-digital-collection/>